Girolamo Marri: Whenever I try to Be Calm I Get an Itch video + sound, 8 sheets of A4 printing paper, on a loop dimensions variable,2012

I mean no disregard, but the currency of introspection is not here. Because we could all go find our inner peace, losing ourselves in the patches of nature left around, breathing qi rather than thin dust, and maybe it would be better than ice cream, but your harmony won’t stop the rest of us doing what we do best: the worst. And yes, you’ll nod so peacefully, holding your brush so delicately, sustaining yourself for a week on a bowl of rice, cleaning with a toothpick, your back like a wooden plank, sipping hot white tea in August and dying with a smile at age 117. But you’re not contagious and you’re not touching anyone; you’re far too slow. If you don’t know it, you’re stupid; if you know it, you’re selfish. So you’re no exception.

The core deficiency of the secret of life in this day and age is that it cannot be tweeted.

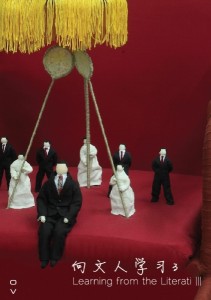

Ji Wenyu Zhu Weibing: “Thoughts on Reading ‘Emperor Taizong Receiving the Tibetan Envoy’” 103 x 69 x 105, stainless steel, wheelchair, and cloth, 2011

Compared to the era of Taizong, our current system appears increasingly antiquated and provides fewer resources for humanity than before. It is spiritually dejected and artistically lacking. This system is becoming more and more overbearing. It stands apart from the proletariat and it is becoming more and more elite. It is system apart from ordinary people; one that is overpowering and arbitrary.

Li Xiaofei: Assembly Line, 2012

Calculating by piecework, calculating by hourly rate, calculating by day

The peacefulness and silence of the details

A fragment and the erosion of a fragment

Like memories on grains of dust

Monika Lin: On the Way to the Imperial Examination… : Crow No. 2, wire, rice paper, paste and beeswax, dimensions variable, 2012

In studying the literati, what is often overlooked is that their privileged life depended on the work of innumerable peasants who created income for officialdom through taxation, appropriated goods and unpaid labor. Using the motif of rice as a signifier for the peasant class, I emulated the practice of the literati by writing the character for rice 米 10,000 times, thereby hoping to illuminate the link between two very different types of labor: the backbreaking physical labor of the peasantry, the countless hours of mental labour (represented by the symbolic number 10,000, or 万) .

Having written 米 10,000 times during my residency at San Francisco’s Performance Art Institute, where I also installed and removed a “field” of rice in a span of 12 hours, I turned my attention to another connection between the literati and the peasantry: folktales. In the tales of Pu Songling 蒲松龄, the Qing Dynasty official who wrote the famous Strange Stories from a Chinese Studio 聊斋志异, Pu uses the plot device of the scholar in various states of accomplishment to lead into morally and psychologically resonant storylines. Often the scholars encounter shape-shifting demons along the way that waylay them or alter their destinies. The fox-spirit, tiger-man and crow are just a few of these supernatural beings whose encounters with wandering scholars not only entertain, but also invite us to reconsider the rich and complex relationship between Chinese folk culture, the peasantry, the Literati and their iconic works.

Shi Jinsong: Shi Jinsong, Writing on the Wall / Writing on Fans, live performance, writing with charcoal on an insignificant wall and on paper fans, 2012

I don't know when the Chinese literati fell into the habit of writing on the wall, and it’s hard to remember what they have written because there are so few famous pieces. Some are about love or grievances, landscapes, personal affairs, prancing around drunk or sober and practicing Buddhism. Satirical verse certainly was an important genre. There were a variety of different forms such as acrostic poems and enigmatic poems. Simply put, the literati probably referred to anything they wrote as “poetry.” Usually they wrote poetry while they were staggering drunk, mostly in brush and ink. Sometimes they would grab whatever was at hand, composing a poem on a bill from a restaurant hotel, teahouse or brothel. Clearly these writing implements would have not been considered first class, but after all, these poems showed the unfettered, free-spirited nature of the literati.

Nowadays we don’t use brushes, and it’s difficult to find traces of their existence. You can’t drink too much or you’ll be in a load of crap, and barely anyone is familiar with the concepts of meter and the tonal patterns of Chinese classical poetry.

But we should maintain these unfettered attitudes. Being surrounded by walls is not cool. It seems that it is essential to write something on the wall, especially the word “anti.”.

So this is the reason I randomly scrawl on these fans.

Su Chang: Su Chang, Portrait of a Tree, plaster and ink, 10 x 10 x 5cm, 2012

Materials have been influential in the development of art. After the Yuan and Ming Dynasties, there was a preference for paper and it was at that time that ink boomed in popularity. In keeping with this tradition, I thought I would try to experience the vitality of these traditional materials.

The ancients had a continuous, long-term, rich and vigorous way of seeing things. Just like a tree in an insignificant place, if we give it time, it can slowly grow into something big and magnificent.

But in our era, we only look ahead; we are reckless and only look for short-term gains. Culturally speaking, we could say that we are in a phase of self-extermination.

So here I paint from memory, from my heart, a portrait of a tree.

Su Chang: Portrait of the Four Gentlemen, mixed media, 80 x 56 x 12 cm, 2012

The Four Gentlemen were just as upright as these fir trees.

Wu Gaozhong: Wu Gaozhong, Book, Me, Rain, Dog, book, 2012

The Four Books and the Five Classics, which I read, was left out in the rain for a night. Then a dog tore it to pieces. I am interested in what kind of encounter occurred between the book, the rain, the dog, and me. On a rainy night, what kind of a relationship was between these four elements?

Xu Zhifeng: Xu Zhifeng, Glass No. 1 Glass, reinforcement steel, concrete 61x17x17 cm, 2012

Industrialization, urbanization and globalization have rapidly changed our living environment. Cement, steel, glass and plastics have become the new “four treasures of the study” or wen fang si bao. These new materials have captivated our new sense of aesthetics, yet can be transposed onto the classical aesthetics. Thus I simply “draw” with these elements and pursue the new “Four Gentlemen” or si junzi in the context of the “traditional” Chinese literati.

-150x150.jpg)

-150x150.jpg)