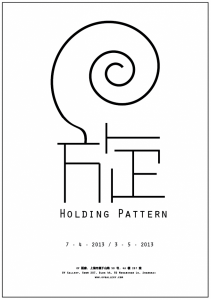

Holding Pattern — Off the Grid

Rebecca Catching

A pattern in its most basic form is something which involves a repetition of a number of elements spaced out in a regular way, to create a form which is often aesthetically pleasing. Patterns exist in nature — snowflakes and spirals would be an example, but the majority of those we see are manmade.

In this show, we are using the term “holding pattern” as a metaphor to examine human behavior — the accumulated actions which we repeat so often that they become second nature to us. We are in a sense, “held” by these patterns and our actions are governed by their principles just as a pattern is governed by its own aesthetic principles.

When we see a piece of polka-dotted cloth, red with white polka dots, we do not question why each polka-dot is white, but if someone were to take just one polka dot and paint it green the whole pattern would be thrown off kilter, and we would question what that green polka-dot was doing, and who made that aesthetic decision.

Zhang Hao creates this effect with his work “One Night with the King,” which features a slowly disintegrating pattern of Middle Eastern motifs. As the pattern fades away, it creates room for an ambiguous object which dominates the foreground — a piece of wood which seems to be wrapped in a black and white patterned shroud. Has someone lain one night with the king? Perhaps? But there seems to be more than this, something of a whiff of a burial here, with an almost corpse-like lump beneath the cloth, where the presence of a body can almost be discerned. In this work, there is something akin to Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s “The Yellow Wallpaper.” In the turn-of-the-century American short story, where the female protagonist is confined to a room upon diagnosis of post-partum mental illness. During her confinement, she becomes obsessed with the wallpaper and then finds a way to crawl behind the wallpaper and enter its world.

Her description of the pattern in the book could speak to not only this work but also the greater themes of this show:

“At night in any kind of light, in twilight, candlelight, lamplight and worst of all by moonlight, it becomes bars! The outside pattern I mean, and the woman behind it is as plain as can be.

I didn’t realize for a long time what things showed behind, that dim sub-pattern, but now I am quite sure it’s a woman.

By daylight, she is subdued, quiet. I fancy it is the pattern that keeps her so still. It is so puzzling. It keeps me quiet by the hour.”

Though Zhang Hao’s work does not offer up any such reading about the medical profession and gender biased diagnoses of hysteria, there is something sinister about his pattern. While at once cheerful and almost cartoonlike, it descends into something awkward and broken towards the bottom of the canvas as if traditions and behaviors are slowly starting to degrade into something twisted and shattered.

This device of layering two images atop each other occurs as well in his other work “Ladies,” which features a television test pattern, rendered in leaden hues (rather than the usual fluorescent pinks and greens, overlaid with a whitewash of ghostly figures. These women stand as if they are in a police line up, only a witness would find it impossible to identify them, as their faces have been completely obliterated — rendered identical by the whitewashing effects of media upon human actions.

But there is something interesting in their poses as if they are facing the charges of some highfalutin parenting association which has deemed them unfit mothers for allowing their children to watch too much television. Media such as television and film play a huge role in the imprinting of such patterns on our psyches, something we see reflected in Zhang Hao’s work “The Politics of Translation” which depicts the iconic Hollywood sign. Originally erected in the Santa-Monica Hills to stimulate real estate development in the region — the sign came to symbolize the seductive power of the movie industry, not only to draw hopeful actors but also to seduce viewers with its values and ideas. Zhang has created a pun on the Chinese phrase “hao-lai-wu” 好莱坞 — the normal transliteration of the word Hollywood which involves the character for good “hao,” “lai” meaning a kind of root and “wu” a sort of landform. Zhang’s new version of “hao-lai-wu” swaps out the characters for different homophones so that it now reads “hobby,” “come,” and “martial arts.” The phrase begins to make a bit more sense when we see that the scene is staged in black and white atop a hill, the likely backdrop of some martial arts film, where we can almost expect two bearded figures to appear from behind a rock, swords blazing. Here Zhang makes a quiet joust at the American film industry, a challenge perhaps to some sort of cultural duel.

Magdalen Wong offers several of her own meditations on media and its influence in pattern making. Her installation “MMM Wow,” consists of a number of television screens placed flat on the ground all playing a video with the light emanating in a small halo around the televisions. The video begins with a short clip of two ninjas laughing, then to a girl eating a cucumber and saying “oh yeah,” while another grabs her hamburger, and through filmic “match on action” seemingly hands it across into another screen to Obama (or an actor dressed as Obama) who takes a bite of a burger. Then a bowl appears on a table and someone says “wah,” and a general crosses his legs while just at that moment his aid sprays his barefoot with some kind of perfume or medicine. This tele-stream of consciousness continues with clowns, la vache qui rit the iconic laughing cow c, a series of child detectives, a woman in a ridiculous yellow polka-dot hat, sumo wrestlers, the Hong Kong cartoon character “laofuzi” or Master Q, break dancers and finally Ronald Macdonald. What the viewer sees, however, is just the flicker of light and the different kinds of exultations, be they sighs of satisfaction, giggles, shrieks of happiness or the distinctly Chinese “wah” which connotes a certain kind of wonder or awe.

By splicing all of these sounds together, Wong lays bare the mechanisms of advertising which aim to work us into a frenzy, presenting us with ideal lifestyles which we should try to emulate, so we too can be as happy as they are. In turning these televisions face down, Wong is helping us to free ourselves from their Medusa-like gaze.

Another video work “Build Break Bricks” features a constant flicker of different images of line drawings created by children overlaid with black brick-like rectangles which slowly climb up the screen and then retreat. The movement of the bricks is complemented by a rhythmic clicking soundtrack almost military in its precision. Somehow one cannot help but think of the morning exercises that children are made to do as a way of instilling discipline or the art classes which focus more on coloring in a solid form rather than creating something wholly new without any parameters.

“Baby Pink Baby Blue,” picks up on this same theme of painting within the lines using a small plastic doll as its subject matter. The baby sits on all fours, while a paintbrush colors-in its diaper distributing pink paint all over it at first and then covering it with a layer of blue paint and so on, until it becomes almost ridiculously large from the accumulations of pigment. The idea conveyed is that the child is of course completely powerless choose his or her sexual orientation. A Canadian couple brought this issue into the public eye in 2011. Kathy Witterick and David Stocker, parents of two boys gave birth to a third child, Storm, whose gender they kept a secret to everyone except their family doctor and the immediate family members. They did this in an attempt to allow Storm some space to decide his or her own gender without being pushed in either direction. The couple’s first two children were very gender-fluid, and often wear dresses and long hair.

As a result, they frequently receive taunting from local children and parents but remarkably they learned to deal with it in an incredibly well-adjusted way, responding to questions about their gender calmly and logically.

Families, in fact, play a very large role in creating and enforcing patterns. This idea comes through in Wong’s work “Chains,” an installation piece consisting of a series of used gold chains which form the structural element of a security chain — the kind one uses when one wants to open the door a crack without letting another person gain entry. Wong has gathered used gold chains, the kind that might be handed down or given as gifts. The use of these “used chains” stresses the ties between family members which create a web — a security net through which no one can fall. At the same time, these chains are also chains that hold, that stop, that restrict movement and certainly certain kinds of actions and behaviors that may be deemed unacceptable in a given family.

Working with this concept of fixed parameters and change, Wong’s installation “Stickies,” adds a playful element of randomness. Despite the patterns and rigid structures which we use to bring order and safety to our lives, fate nonetheless steps in to add a playful element of unpredictability. Her installation work consists of a series of sticky notes with different words written on each note to form a sentence. When a guest removes a note, a new word appears but the sentence is still a sentence, only with a different meaning. The pattern of the colored stripes, blue, pink, purple and yellow remains the same but the content of the sentence may change from “You think I missed her” to “I believe you saw him.” In a sense, it’s like our lives: we are cut from a certain kind of mold but we may constantly find ourselves in different situations replicating the same behavior with different people.

Li Haifeng’s work, “Waiting for Godot,” echoes this theme of behavior and reinforcement, featuring a crowd of people happily applauding, very much like the cast of “MMM Wow.” A group stands around a banister clapping towards an unknown area as if something momentous has just happened. It could be a child taking its first steps, a couple getting married — any event, small or large, which receives some sort of public recognition. Li has titled the work, “Waiting for Godot,” after Becket’s absurdist play. Though Becket did not mean for the word “Godot,” to be a stand-in for “god” (the original play was written in French where the word for god is “dieu”) there is a definite existential connotation to the play and the work. We as humans want to be rewarded. We want to be praised to be told that what we are doing is right that our lives are meaningful, that our repeated actions on earth amount to something more than an attractive pattern.

His other work, “Bridge,” offers a poignant counterpoint. From the center of the picture plane juts a long board which looks like a dock or a diving board — leading one into the middle of a lake. It has the same sense of “event” or “performance” as “Waiting for Godot” and the same lack of a central figure or action. In this work, Li employs a similar technique although the medium is slightly different. All of the forms in the painting are constructed through layers and layers of spirals, circles — taking the concept of “holding pattern” into aesthetic territory. But where “Bridge” differs from the first work is that it seems to offer a different path, way to leave the pattern, to dive off the dock and swim off in a different direction. And it’s from this jumping off point that we begin to examine the reverse side of this pattern the “non-pattern” so to speak and the works of Jiang Guozhe.

The characters in his paintings are all children and have had less time to be conditioned by the mechanisms of society. The patterns bear only a light imprint upon them at this stage. They are surrounded by what looks like semi-natural semi-urban environments engaged in games of imagination.

“Cloud, Moon, Light,” features two boys playing what looks like some kind of shadow boxing with costumes and props, in an ambiguous realm of shade, trees, and walls. While the ironically titled “Spring,” depicts a child emerging from the mouth of some kind of sewer or factory pipe. Here children are using their powers of creativity to turn the grim city surroundings into their own imaginary kingdoms.

In “Welcome,” for instance, two girls throw up their elongated arms in a gesture of pure delight. Interestingly Jiang Guozhe has rendered them in an almost childlike painting style, which is surprisingly devoid of color. Meanwhile, the wall behind them is covered in abstract chromatic exultations — similar to those found in “Build Break Bricks” — as if the children’s imagination has been drained from them and deposited on the wall behind them.

Meanwhile, “Ice Cream,” offers a very different portrait of childhood. Again two girls stand side by side in front of a low wall, one cast in a yellow light, one cast in red, both are posed with ice-cream in their mouths but both looking up fixedly at the viewer as if someone has barged in on some intimate girlhood moment. The presence of the play structure and decapitated merry-go-round horse appear to act as signifiers of innocence, but they seem to be painted on like poster or backdrop rather than rendered as a realistic background. There is something about the way the girls stare at us transfixed, the lurid yellow and red, that creates a sense of discomfort — putting the viewer in the role of an intruder.

In a way these girls are just embarking on a series of lifetime adventures of learning the pattern, and making mistakes, getting reprimanded by adults, and maybe, finally when they grow up, creating their own unique patterns, or even a series of patterns to adapt to each stage of their life. While a typical airport holding pattern is shaped like an oblong racetrack and is thus fixed, human patterns need the flexibility to change, especially when they become pathological, to adjust to the infinite possibilities and challenges of human existence.

花纹最基本的形式是重复, 大量的元素有规律地排列, 用以创建一种通常赏心悦目的模式。花纹通常出现在大自然、雪花和螺旋等形式中出现, 但我们所见到的多数都是人造的。

在这个展览中, 我们使用 “回旋” 作为一种隐喻来研究人类行为 — 我们太过频繁地重复这些动作以至于它们业已成为我们的第二性, 在某种意义上, 我们被这些花纹 “把控” (有时被它们压制), 我们的行为受制于它们的规律, 就像花纹的美感也受制于美学规律。

当我们看到一块圆点布, 如果是红白相间的圆点花纹, 我们不会问为什么每个圆点都是白色的, 但如果有人将其中一个圆点染绿, 整个模式都被打乱了, 我们会问那个绿点是做什么用的, 为什么会决定用这种颜色。

张灏在她的作品 “与王一夜” 中创造了这种效果, 其特征是慢慢瓦解的中东图案。当花纹逐渐消退, 一个模棱两可的对象控制着前景, 一块黑白相间的裹尸布里似乎包裹着一块木头。是不是有人和王睡了一晚?或许?但看起来这里不只是这样, 肯定埋葬了些什么, 像是布裹着一具尸体, 但我们察觉不到身体的存在。在这个作品中, 有类似于夏洛特.吉尔曼的 “黄色壁纸”, 女主人公被禁锢在一个房间里做产后精神疾病的诊断。在她被囚禁期间, 她沉迷于壁纸, 幻想自己可以爬到壁纸的后面, 进入它的世界。

她在书中对于花纹的描述不仅能说明这个作品, 还有关于这个展览更大的主题:

晚上在任何形式的光的照耀下, 在黄昏, 烛光、灯光, 最糟糕的是在月光下, 它变成了一条条! 在后面的图案, 很明显是一个女人。

很长时间我都不知道后面展示的是什么东西, 花纹后面昏暗的东西, 但现在我很确定这是一个女人。

在白天她是柔和的, 沉静的。我猜想是花纹令她纹丝不动。这如此令人费解, 在那一小时里它让我很安静。”

尽管张灏的作品没有提供有关医学界以及歇斯底里的性别偏见诊断, 他的花纹有一些邪恶的地方, 而立刻又愉悦起来, 近乎卡通样式, 陷入一种尴尬, 然后在画布的底部破碎, 似乎传统和行为正在逐渐地消解。

两个图像互相交叠的技巧, 也出现在他另一个作品 “夫人们”, 其特征是电视测试模式,呈现在沉闷的色调中 (而不是通常的萤光粉红或荧光绿, 前方站着一排白色的幽灵般的人物。这些妇女站成一排, 像是等着受害者辨认谁是罪犯, 但目击者无法识别她们,

因为她们的脸已经完全消失, 暗示了媒体在人类行为中所起的洗白作用。

但她们的姿势有一些很有趣的地方, 像是她们正面临着育儿协会一些夸张的指控, 认为这些母亲不该让她们的孩子看太多电视。

媒体, 比如电视和电影, 将这些模式深深地烙印在我们的心理层面, 这是反映在张灏的作品 “翻译的政治” 中的元素, 他描绘了好莱坞标志 (最初竖立在圣莫尼卡山用以刺激这个地区的房地产发展) — 这个标志象征着电影业的诱惑力, 吸引着想要成为明星的那些人, 并且以它的价值观和想法来吸引观众。张灏创造了一个中文的短语将 “好莱坞”正常音译为 “好来武”, 他的版本的好莱坞使用中文的 “爱好”、“来”、“武术”。 当看到场景位置是在山上, 且是黑白背景时, 这个词便开始更有意义, 在一些武打电影中, 两个长着胡须的人物出现从岩石后面, 剑光闪烁。在此张灏与美国电影业进行了一场安静的角逐, 一种也许是为了某种决斗做出的挑战。

黄颂恩提出了自身对媒体的一些思考及其对制定模式的影响, 她的装置 “恩…哇…”, 数个播放着录像的电视机平放在地面上, 每个电视机外沿都有光圈环绕。视频开头两个忍者在笑, 一个吃黄瓜的女孩说 “哦耶”, 随即切入另外一个屏幕(或是一个很像奥巴马的男演员), 咬了一大口汉堡包, 电影的技巧为 “匹配行动”, 相似的手奥巴马(或一个演员扮成奥巴马把一口一个汉堡)。然后桌子上出现了一只碗, 有人说 “哇”, 就在这时候一个长官翘起了腿, 他的警卫员在他光着的脚上喷了某种香水。这个电视流的意识在小丑中延续, 笑牛牌(法国芝士), 几个孩子打扮得像侦探一样做广告, 一个头戴荒谬黄色圆点帽子的女人, 相扑手, 香港的卡通人物老夫子, 和麦当劳叔叔一起跳霹雳舞。观众可以看到的不过是闪烁的光和不同种类的欢呼雀跃, 它们可能是满意、笑声、幸福的尖叫声或典型中国式的 “哇”, 似乎缺少了英语的哇里所包含的某种惊讶或敬畏。

通过拼接这些声音, 黄颂恩赤裸裸地揭露了广告的机制, 其目的是为了让我们为之疯狂, 将理想的生活方式呈现在我们面前, 怂恿我们应该尽量模仿, 这样我们也能和他们一样愉快。通过将这些电视机翻面放置, 帮助我们摆脱他们的 “梅杜萨”(希腊神话里的女妖, 只要她的眼睛和人对视就可以石化那个人)。

另一个录像 “把砖头搭起来, 再打碎” 作品特点是不断闪烁的由孩子们创造的不同素描与黑色矩形砖块相覆盖, 慢慢爬上屏幕。一个有节奏的敲击伴随着这些转块的运动, 如同整齐划一的军事操练。不知何故情不自禁地想到早操, 孩子们被灌输各种纪律或那种一早已将形式固定, 让孩子们照搬上色的艺术课程, 而并没有引导他们不依赖任何参数创造一些全新的东西。

“浅粉红色淡蓝色”, 探索了与在线条内的绘画一样的主题, 借由一个小塑料娃娃作为它的主题。婴儿匍匐着, 与此同时一支画笔在它的尿布周围涂满了粉红色的颜料, 然后再覆盖上一层蓝色的颜料, 直到颜料堆到几乎离谱的程度。作品传达出这样一个想法, 孩子当然完全无力选择他或她的性取向。有趣的是2011年加拿大的一个事件引出了这个话题。一对夫妇, 凯西.维特瑞克和大卫.斯多克, 这两个男性作为父母又生了一个孩子, 名叫 “风暴”, 它的性别是一个秘密,除了他们的家庭医生和直系亲属以外, 无人知晓它的性别。他们尝试给风暴一些空间, 在不受任何一方压力的情况下, 自由选择自己的性别。这对夫妇的前两个孩子, 两个男孩对性别已经有着自由的想法, 留长发, 穿裙子。结果当地的孩子及其父母经常嘲笑他们, 但这两个引人注目的孩子早已学会以令人难以置信的自我良好调适的方式, 平静地很有逻辑性地应对他人对其性别的质疑。尽管这个家庭被右翼脱口秀成员狠狠地批评, 我们却欣喜地看到他们业已开放了对话的空间。事实上给儿童创建一个中性的环境是很难的, 从儿童的衣服到玩具商店都早已经以颜色做了性别编码。

事实上, 家庭在模式创造和实施中发挥了非常大的作用。这个想法贯穿在黄颂恩的作品 “链子” 之中, 一件由一系列金链子组成的装置作品, 形成了链条锁的结构 — 开门时, 会有一条缝, 但是人是无法进入的。黄收集了用过的金链,一部分可能已被转手过数次, 有些用作礼物。使用这些 “用过的链子”, 强调了家庭成员之间的关系网 — 保护着每个成员的安全网。同时这些链条也阻止着, 中断着, 限制着行动, 当然某些行动和行为可能对一个特定的家庭来说是不可接受的。

黄颂恩的作品 “便条纸”, 探索了模式这一主题, 并且增加了随机这一元素。在某种意义上它是对生活的一个有趣的比喻。尽管强加给我们的模式和刚性结构给我们的生活带来秩序和安全, 不过却增加了一个随机的元素。她的装置作品由一系列写着不同单词的便条纸构成, 然后组成一个句子。当观众撕掉一张便签, 一个新单词出现, 句子仍然成立, 但意义却不同了。彩色条纹的图案, 蓝色、粉色、紫色、黄色是相同的, 但句子的内容可能从 “你想我想念她”。变成 “我相信你看见他”。在某种意义上, 它就像我们的生活, 是从某些类型的模具上切下来的, 而我们却不断地发现自己在不同的情况下和不同的人重复同样的行为。

李海峰的作品, “等待戈多”, 呼应了行为和强化这一主题, 特点是一群人高兴地鼓掌, 很像是 “嗯哇” 的投射。一群人站在栏杆前和向着一个未知的区域鼓掌, 好像刚发生了重要的事情。可能是一个孩子初出学步, 一对夫妇结婚 — 任何受到公众认可的小型、大型的项目。李将作品命名为 “等待戈多”, 贝克特的荒诞剧, 两个人演着等, 等, 等着一个人不会来到的人。尽管贝克特并不在诠释 “戈多” 这个词, 是站在 “上帝” 的 (最早这个剧本是在法国写的, 法语 “上帝” 是 “dieu” 不是 “god”) 这个剧和作品有着一个明确的生存内涵。我们作为人类想要奖励, 我们希望被赞扬被告知我们所做的是正确的, 我们的生活是有意义的, 我们在地球上重复的动作是有意义的。

他的另一个作品 “桥”, 呈现了一个引人入胜的对位法。作品的画面中心架起一块长板, 看起来像一个船坞或跳水板 — 引领人们来到湖的中心。它与 “等待戈多” 在 “活动” 或 “表现” 上具有相同的意义, 同样缺少一个中心人物或动作。在这个作品中, 李还借用了一个类似的技术, 虽然媒介略有不同。所有的绘画形式都通过一层层的螺旋形、圆形构成 — 将 “回旋” 这个概念迁入美学领域。但与第一个作品 “桥” 不同的是, 它似乎提供了不同的路径、方法来离开这种模式, 潜水离开码头, 向不同的方向游去。然而从这个起点, 我们进入这个展览的另一边。姜国哲的作品, 让我们进一步跃入无人地带 — 这个领域, 越过模式, 摆脱禁锢, 最后离网。

他画中的人物都是孩子, 他们较少受制于社会的机制。在这个阶段, 只有光这一模式印刻在她们身上。他们的周围看起来如同想象力游戏中的半自然、半城市环境。

“云, 月, 光” 中两个男孩在一片模糊的树木和墙壁的阴影中摩拳擦掌且搭配有服装和道具。而另一个作品戏谑地题为 “泉”, 描绘了一个孩子从下水道或工厂管道口中滑出。在这里, 孩子门正运用它们的想象力和创造力将严峻的城市环境环绕进入自己的假想王国。

在 “欢迎” 中, 两个女孩挥舞细长的手臂摆出一个纯喜悦的手势。有趣的是姜国哲使用了一个几乎天真烂漫的绘画风格, 但异常黝暗, 而她们身后的墙上覆盖着抽象的兴高采烈的彩色 — 类似于在 “把砖头搭起来, 再打碎” 中所看到的 — 如同孩子们的想象力从他们那流失了, 堆积到身后的墙上。

与此同时, “冰淇淋”, 提供了一个截然不同的童年的肖像。两个女孩并排站在一个低墙前面, 一个被投射在黄色的灯光下, 另一个在红色灯光的映衬下, 她们都将冰淇淋含在口中, 但同时都抬头盯着观众, 像是有人闯入了一些亲密无间的少女时代。滑滑梯和被斩首的旋转木马的头部似乎意味着无辜, 但他们更像是被印在海报上而并非以一个现实的背景显现。女孩看到我们惊呆的眼神也带出一个问题, 背景中的黄色和红色, 创造出一定意义上的不适感, 让观众不禁联想到一些猥琐的老男人、男性观众, 或其他一些人物, 导致这些女孩悲痛, 扰乱了她们童年的幸福时刻。

从某种意义上说, 这些女孩只是着手进行着一系列生活冒险, 学习模式, 犯错误, 受到大人们的训斥, 也许当他们长大后, 能创造出自己独特的模式, 甚至是一系列的模式, 以适应每个阶段的生活。而一个典型的回旋模式的形状像一个长方形的赛马场, 因此是固定的, 人类模式需拥有如同回旋离网的潜力和韧性, 如此才能更好地成长并且适应生活给出的无限的可能性。