A Tribe of One

Negotiating the Difficult Terrain Between Collectivism and Individualism

Rebecca Catching

While the post-60s and 70s generation in China, was extremely group-centered and communal spirited, each subsequent generation, the post-80s, and the post-90s became successively more and more individualistic. The young independent spirited post-90s couldn’t be more different from their parents, many of whom still possess a strong nostalgia for “red culture” and collective activities.

In the context of this clash of values, it makes sense to re-examine the concepts of collectivism and individualism, what these concepts mean at a fundamental level, and what kind of a society they help to create.

In the 1960s and 1970s Dutch Socio-Anthropologist Geert Hofstede conducted an extensive survey into the social values of various nations. Working for IBM at the time, he interviewed IBM’s employees about a variety of issues, everything from power to indulgence to individualism. His findings about individualism will not shock most people. Most developed Western countries scored high with Canada at 80 out of 120 and the US at 91 on the individualism index, while developing countries brought in scores as low as 14 for Indonesia and 6 points for Guatemala.

As the study reveals, there is a fundamental difference in the way various people operate within the social context. Hofstede sees individualism as: “a focus on rights above duties, a concern for oneself and immediate family, an emphasis on personal autonomy and self-fulfillment, and the basing of one’s identity on one’s personal accomplishments.” ¹

At the same time, if the individual fails to perform, society is not to blame and those who succeed despite difficult odds are deified for having “pulled themselves up by their bootstraps.”

Individualists also have different attitudes towards relationships, choosing to abandon them when they become too time-consuming or too much of a burden, whereas collectivist see relationships as obligations and mutually binding. Collectivist cultures focus on these “vertical relationships” between superior and inferior whereas individualistic cultures focus more on relationships between friends or equals.²

In fact, for collectivists fulfilling social roles, such as for instance buying one’s parents a house, bring a personal sense of satisfaction, more so than individual accomplishments.³ Interdependence is key and conflicts between individuals are suppressed – i.e. the elephant in the room is allowed to remain there unacknowledged.

Though individualists may be more open to discussing problems, they are also more likely to become depressed. The focus on the individual means that people do not have the luxury of ruminating on their own problems, which often leads to depression.

Monika Lin explores this territory of mental health looking at the situation in her home country, America — where depression and anti-depressants are rampant and where individuals struggle to conform to a psychological mean or average — to weed out any unpleasant feelings and be “happy like everyone else.”

Concepts of psychological normalcy have lead to the medicalization of many common emotions experienced by the general public. While, for instance, things like public speaking or worrying about work are fairly common amongst mentally-healthy people, these emotions have now been branded as “social anxiety disorder” or “general anxiety disorder,” diagnoses which were considered quite rare in the 1980s but now have seen a huge bloom of cases which was due partially to the promotional activities of pharmaceutical firms.

In his book, The Medicalization of Society: On the Transformation of Human Conditions, medical sociologist Peter Conrad states that up until 1997, there was a US requirement for drug manufacturers to list all side effects – requiring the announcer at the end of a commercial to hurriedly reel off a bunch of symptoms: i.e. “Scamitol could cause heart and liver failure, purple-colored rash, hallucinations, tingling sensations, anal leakage, and temporary blackouts.” Now drug makers have eliminated the frightening elements of these ads by adding a toll-free number or website, where if a patient is informed, they can go to look up side effects. 4

This lead to a strange situation where big pharma was fueling medicalization in order to sell more drugs. For instance, when GlaxoSmithKline experienced slow sales of the anti-depressant Paxil, they lobbied for their drug to be used to treat social anxiety disorder and general anxiety disorder – then proceeded to fund marketing campaigns which were thinly disguised disease “awareness campaigns.” 5

For the “Double Happiness Series,” Lin began her investigation in Kansas City and San Francisco where she interviewed people in her community who had been diagnosed with mental illnesses and were taking behavior-altering drugs. She collected samples of their medications and made plaster casts of their pills laid out in intricate patterns encased in resin and laid over with images of joyful, faceless children skipping across prosaic or shall we say Prosac-ic landscapes. Her color palette is both idyllic and sinister with lemon yellow backgrounds contrasted by with deathly grey flowers, or light pink poinsettias contrasted against a blood-red field of color. In “Kicking Boys, No. 7, ”2005, we see dark coffee-colored expanses dotted with lime green pills and images of bacteria under the microscope – a reference to how scientific imperialism, and how science is used to govern individual’s behavior.

These kinds of “Brady Bunch” vignettes of childhood feature prominently in the advertisements of psychotropic drugs used to govern behavior and the figures in her paintings are rendered in a simple, almost cartoonish style. But unlike cartoon characters, they are faceless – drained of emotions by the sinister effects of the pills. While Lin’s Ritalin boys are acting out (sending roundhouse kicks into the air), the girls are skipping and playing, though often we see images of the girls slowly fading into nothingness – traces of their outlines like ghosts of their former selves.

From this land of collective psychological conformity, we jump to the great social collectivizer of China, the “danwei” or work unit, with Chen Hangfeng’s “Cups” 2010 installation. The 60s-era danwei was in control of many aspects of one’s personal life, such as housing and family planning. The piece consists of a series of chabei or tea containers, the kind typical of older government-style work units but conspicuously absent in most modern multinationals – save for the guardhouse.

Chen collected the cups from a number of different staff lounges in Shanghai, namely a supermarket, a factory, and two pharmacies. He engaged with the management and workers of these danwei, asking for their cups in exchange for money, but most of the staff gave them up for free, handing over their used Tang and Nescafe coffee jars, or the popular Lock Lock brand of Tupperware jar, with a filter to keep the tea leaves out. While all of the staff owned cups, each cup was different, reflecting the DIY creativity and resourcefulness of the working class, which harkened back to an era where resources were scarce.

Chen arranged the cups on a small table and filled them halfway up with water. A small hammer was hooked up to a mechanism to strike the bottom of the table repeatedly. The hammer sends vibrations up through the table into the containers and the ripples in the water are reflected on the wall behind the installation.

The light shining on the cups gives them a special aura – putting them in the spotlight, like honored guests against a backdrop. At the same time, the cylindrical shapes and reflecting light makes appear like votive candles – the kind lit for prayer or at a vigil – the reflection on the wall a kind of testament to the human spirit, an aura which shines through the shabby and scratched exterior of the glass. But the subtle knocking of the hammer, however, adds a somewhat sinister element – a dull thudding – violent in contrast to the gentle, shimmering light on the opposite wall. Chen uses the hammer as a stand-in for the forces, which have the power to affect the lives of the masses, natural disasters, inflation, economic downturns and the like. Its effect is subtle yet unsettling and speaks to the relative lack of security in comparison to the old era of “danwei” where jobs were for life and rice bowls were made of iron.

Qian Rong’s new sculpture and painting works also harken back to an older collectivist era. The starting point for this piece was a photograph of a number of older laobaixing or working-class people, singing along the banks of the Yellow River in Shaanxi, not too dissimilar to the flourishing of choral groups which broke out this July in the parks of Shanghai to celebrate the 90th anniversary of the party. Hearing these old crooners in the park is enough to tug at the heartstrings of even the most calcified cynic, the singers warbling voices brimming with passion and nostalgia. Perhaps these singers yearn for a slower era, one less concerned with material accumulations, an era which was, at least on the surface more egalitarian.

In Qian Rong’s work, we see these two paradigms clash, the current era represented by “Ahead of the Collective,” 2011 a group of sinister-looking suited men grasp onto a number of strings. These men were inspired by a photograph, which Qian found in a newspaper featuring the mugs of a number of the richest men in China with the words “This Year’s Troublesome Wealthy [Elites].”

To the right of the painting is a small box, which contains a vampy-looking woman making eyes at a man wearing a dunce cap. In the back, the word “Confess” is written on the wall.

The companion piece to this work “Small Collective, Big Alliance,” 2011 features a square box full of cubbyholes, in which sit a variety of characters, some businessmen, some intellectuals, some ancient sages, most seem to look distraught as if they too have been called out and asked to confess. Guarding them on the right is a grimacing dragon and a man in a “zhongshan zhuang” or “Mao suit” with a stern look on his face. When placed together with “Ahead of the Collective,” 2011, the group of men, on the left, look as if they are holding ropes attached to the agglomeration of cubbyholes, thus controlling their fate.

The cubbyhole motif conveys ideas of confinement, but also display presentation and framing (both in the literal and criminal sense). Accompanying these paintings are two three-dimensional cubbyholes, “Small Collective No.1 and No.2,” 2011 made out of stainless steel sheeting which contain small sculptures made out of fiberglass. The effect is something of a mix between a diorama and a time capsule where the present and history occupy the same space. Qian’s sculptures include a panda in a military greatcoat, a small bust of a stern-looking businessman and a bank of cubbyholes out of which poke small panda faces. The panda known as a “national treasure” represents the more cute and cuddly side of collectivism and along with the wooden eagle statue, and a plastic toy pig sporting large breasts and a thong, add a touch of absurdity to a more serious comment on power.

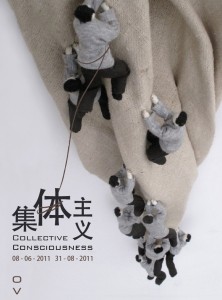

Though we often think of a collective as a monolithic group, which works together to achieve the common goals, there are many dynamics within that group which are, in fact, working at odds. Ji Wenyu and Zhu Weibing look at these conflicts in terms of the idea of social mobility. On top of a rough piece of gunnysack cloth, are a number of small cloth figures, “xiaoren” in Chinese. ( I mention this word as it references the Confucian concept of “xiaoren” which means someone who is petty or small-minded and driven by personal gain. )

The artists’ “xiaoren” hold tightly on to the cloth as if waging some kind of epic tug-of-war. At the bottom of the cloth, which tapers gradually to a point, are another group of xiaoren agilely making their way up the cloth with the agility of professional stuntmen.These ambitious upstarts are putting weight on the cloth, thus threatening to pull other xiaoren down on top of them. Using a very simple visual form, Ji and Zhu capture one of the major struggles of any society, even the art world, the fight of the established to stay entrenched in their positions while the young, or underprivileged attempt to scramble in through a hole in their defences.

Those on top are, understandably, quite reluctant to give up their positions and swap spots with those down below. In understanding this work, it’s useful to understand the concept of “relative social mobility” which denotes an improvement in one’s salary year on year, whereas “absolute social mobility” gauges one’s mobility in comparison to their peers. If one person gets hired to be the CEO of a company, his absolute social mobility improves, but his friend, who is still working as a sales manager sees a decline in his absolute social mobility even though the friend’s salary is still the same – in short, the friend will end up holding the short end of the gunnysack. The use of the material – which is rough, durable and fairly cheap conveys ideas of climbing out of poverty and trading one’s flour-sack dress for a slinky Christian Dior shift.

The concept of the individual as an active agent in society plays a central role in a new series of paper cuts by Ed Pien. Entitled “Regeneration,” “Redemption” and “Rebellion,” the works negotiate the unpredictable territory of the human mind in its calculations over whether to join the collective or break free from it. The cult of Ayn Rand believes that we should break free from the collective, promoting a kind of social Darwinism, an “ethical egoism,” Rand positing that it was moral to act in our self-interest, while others, such as Auguste Compte espoused of the philosophy of “altruism,” that it is our moral duty to put the needs of others ahead of those of ourselves.

The figures in Pien’s work seem to be acting out the mental gymnastics of this decision through gestures and body posture. In “Regeneration,” the figures are tentatively walking around in the branches of the tree, which with its expansive arms, symbolizes an embrace. At the same time, the tracery and the interconnectedness of the branches convey a sense of rivers, roads, arteries or networks – things that link people together.

In “Redemption” we see a figure making a strident break from this network and jumping out of the tree, breaking branches on the way and causing shards of twigs and bark to fall from the tree. Two birds circling overhead seem to convey a sense of surveillance but could also imply freedom and independence.

In “Rebellion,” the tree has transformed itself – sprouting houses out of its branches. Two figures in the trees strike menacing poses, like thieves waiting in the bushes and throughout all of the works, creating a kind of awkward disconnect between the figures and the trees. They seem to be on a different plane, and of a different scale. The humans never really seem fit in – or purposely chose not to fit in, living as egoists within the realm of the society.

There is also an interesting symbolism in the idea of “man coming down from the trees,” how human evolution and the change from tree-dwelling to plains-dwelling signaled the beginnings of human civilization. Something about the work though seems to indicate, that even though we’ve been civilized, man continues to act as his own agent, a lone wolf rather than part of a pack.

Man’s independence and interdependence is also a prime concern of Robert Davis in his mixed media painting series “Meditations,” which urge us to be a useful part of the collective – to take an active stance in terms of using our individual power to solve collective problems.

Water has, for a long time, been a motif in Davis’ work and this recent series looks at rising sea levels which no doubt brings up the ideas of sinking, islands, and isolation. He was inspired by 17th century poet John Donne who exhorts to think of the whole of humanity as a body (in “No Man is an Island”) – when one person dies it’s as if we lose a finger or a foot – we need to be equally concerned for others as we are for our own wellbeing.

“As therefore the bell that rings to a sermon calls not upon the preacher only, but upon the congregation to come, so this bell calls us all; but how much more me, who am brought so near the door by this sickness.”

By using the metaphor of the death knell, he adds a morbid urgency to this plea to consider the plight of mankind which seems strikingly relevant with the current climate change crisis. The large buildings and structures in his painting look as if they are sinking into the enveloping white expanse of water, and it appears that it is almost too late.

In “Meditation II: A Collective Consciousness” 2010 Davis sketches out more clearly this conflict between the individual and the collective with a man straining to hold a guy-wire attached to the left smokestack of a factory while another group of men pulls on the right smokestack. These wires create a visual and a metaphorical sense of tension: the competition between humans to exert their will over one another and the moral struggles which play out in the mind of the individual between generosity and selfishness.

Though the mass of buildings looks like one singular object, perhaps Photoshopped and printed out, it is actually an agglomeration of different images, cooling towers, factories, old European looking buildings – all painstakingly cut from newspaper photos. Davis spends an inordinate amount of time rifling through newspapers, as he has to find original images of buildings of the same scale.

The individual cutouts are unified through application of pencil, pen, and ink and Davis adds in bits of text such as “I don’t blame the individual for being absorbed into a culture” and “Think independently and learn to make choices,” text which is almost imperceptible but give a human dimensions to the newspaper photographs. Davis’ work requires that we strain our capacities of attention to pick out the evidence of the hand of the artist in something which looks like, from a distance, to be wholly machine made.

Ironically because his writing and the details are so small, they can sometimes be viewed more easily after being photographed and magnified by computer. This contrast between the large, manmade and institutional and the human and the personal is a theme which Davis has explored in previous works – seeking to remind us of the value of the individual in this great economic machine.

Li Xiaofei examines the conflict between the man and the machine in his captivating video works “Foreign Boss” 2010 and “A Workshop Director,” 2010. These works are part of a larger practice of the artist which began in 2009 where interviewing primary school students in France and in China asking them basic questions about their lives. In this series, Li interviews a number of different people who work in various factories in the Yangtze River Delta, a printing shop technician, a fabric workshop director and the foreign boss of a printing company.

The interviews begin with the subjects explaining something about their job, about the equipment in the factory, what is produced there, and then go into more personal territory, with talk about what the subjects do on weekends or how much time they have off. What becomes clear is that their private lives have been subsumed by the needs of the factory, and even when they do have time off, their social life seems constrained to the occasional outing or chatting with friends online.

This notion of intrusion of work life into private life is underlined by Li’s rapid-fire editing. As soon as the sentence has come out of the subject’s mouth, the scene cuts to rapidly spinning coils of paper or grinding drums which thread patterned fabric down the assembly line. The quietness of the interview room is shattered by the roar of machinery, intruding on the conversation. There is an interesting contrast between the gleaming polished steel and the taut reams of paper, the geometry power and precision, and the somewhat lackadaisical unpolished nature of the humans behind the machines, the foreign boss with his shaggy hair and or the print shop worker who blinks in time with the rhythm of the paper stacking machine.

The dialogue of the foreign boss also emphasizes the contrast between working life and private life, explaining how Europeans have a much healthier work-life balance whereas in China employees are expected to be always on call and always available for overtime. The boss contrasts this to the days of collective work units where jobs were secure and everything is provided. Today’s new work units are more demanding and less forgiving. While employees are not held after work for study sessions in the new capitalist model, they stay after work because the factory demands it or they need to earn more money. Are they working to live or living to work?

Sometimes we fall into fixed patterns and soon our actions become subconscious and automatic; João Vasco Paiva examines issues of mimicry and repetition in his installation work “Chirps. VII: John in the Cage” 2010. Chirps consists of a number of electronic birds which emit a series of chirps – with a real myna bird which, over time, learns to imitate their sounds. Though mynas have adapted to mimic other birds in the forest, they will easily latch on other household sounds including mobile phones and whirr of a microwave – one myna in Shanghai actually learned how to mimic the sound of an old man clearing his throat.

Like the myna bird, composer John Cage also took delight in ambient sounds and is well known for his controversial composition “4’33” – a 4-minute long rest created in order to have the audience contemplate the ambient sounds of the venue.

When the myna – learns how to mimic the electronic birds in his flock, his movements and chirps are recorded by electronic devices and this feedback regulates how much voltage the birds receive. Here Paiva plays with the irony of nature imitating a manmade object, which is itself designed to imitate nature.

John Cage – the bird – though leading the orchestra is also following it, all which gives us an interesting metaphor for group dynamics – how any leader, no matter how strong, is governed by what is considered acceptable to the group.

This feedback loop also provides interesting insight into how we process, pass on or re-tweet information. The fact that mynas repeat even sounds which are not words lends interesting symbolism to the theme of the show. How often have we found ourselves repeating something without really investigating it’s verity, only to have it be passed around, change forms and show up again in a different guise. For instance, in contemporary newsgathering, items tweeted on microblogs such as Weibo are getting picked up by mainstream newspapers and then these articles are getting tweeted by readers – what were the sources of these tweets and did anyone investigate their credibility? During the exhibition, the work also acquired new meaning when John Cage (the bird) began to make strange sounds. He had actually begun to pick up some of the sounds in the exhibition, namely the voice of Li Yang, shouting repeatedly in Zhou Xiaohu’s “Crazy English Camp Tate,” 2010 video. The owner of the bird shop, where we had negotiated, the rental of the Mynah was quite perplexed by this new vocabulary.

This played right into the theme of mindless repetition seen in Zhou Xiaohu’s performance video, which was based on an unconventional English school started by the charismatic Li Yang – a Mainland English school mogul who is part language teacher, part motivational speaker and full-on zealot who became a phenomenon in China in the 1990s. The secret method of crazy English is to have students shout out sentences at top volume so they can overcome their fears.

The program has been criticized by some as a Crazy English a cult lead by a demagogue. Author Wang Shuo described it thus: “It’s a kind of old witchcraft: summon a big crowd of people, get them excited with words, and create a sense of power strong enough to topple mountains and overturn the seas.” According to Evan Osnos in an article in the New Yorker, the program also has quite strong nationalistic overtones: “Conquer English to Make China Stronger!” Li Yang’s cosmology ties the ability to speak English to personal strength, and personal strength to national power.” 6 Osnos goes on to describe the crazy English Camp he visited in Beijing as having a military flavor with instructors in fatigues and banners with nationalistic slogans. No doubt the similarities to the oratory flourish of other totalitarian regimes is hard to miss.

In his performance Zhou sought to invite the inventors of Crazy English to do a performance at the Tate, this time using British students, mostly native speakers as his students. The instructor uses extremely exaggerated movements and expressions, asking students to say words with the same vowel sounds i.e. “time,” “like” and “fly.” They repeat them over and over waving their arms around in the air shouting time-like-fly, time-like-fly over and over again. The routine continues with “Oh” and “So” stretching out the sounds with a wailing voice which makes him seem like a dolorous ghost. Absurdity is piled upon absurdity when he uses the gesture of slitting a throat to mime the word “crazy.” Some of his gestures even border on the obscene, such as a sideways victory sign placed beside the mouth (which many might interpret as lewd) or having the crowd shout the word “come” repeatedly. The piece also features a series of interviews with the participants afterwards in which they discuss things such as the sexual innuendo, the sense of being manipulated and one respondent (a non-native speaker) even discusses the issue of how he felt shy and how speaking in a group helped to overcome his shyness.

The sense of cultural alienation or strangeness is highlighted by the set of the performance which is decked out in banners which read [sic], “Help 300 million chinese speak good english. Make china widely heared throughout the world.” The instructor’s pronunciation is also fairly accented, a trait which comes out when he shouts out the word “misanthrope.”

By making Westerners learn Chinglish, Zhou Xiaohu seeks to turn the tables and upset the power balance between China and the West in a kind of postcolonial critique of a system which requires the peoples of the world to learn English while English speakers generally make little effort in return. But at the same time, the work is also about cultural exchange of another sort, the exchange of Chinese collective styles of learning (think morning calisthenics and singing of red songs) to a Western audience.

Virginie Lerouge Knight explores a fascinating continuum between individual and collective with her installation work “Individuals Shine Differently” 2011. A light bulb on the wall is attached to a dimmer which can be turned to the right or left to adjust the amount of light. When the light is turned to its brightest, the body of the viewer casts a shadow on the wall. On the wall beside the dimmer are a series of words:

Individualism Collectivism

Maverick Follower

Selfish Caring

Original Traditional

Creative Conformist

Shining Modest

The light bulb as a symbol conjures up many things, the idea of light being associated with talent, charm or intelligence. Phrases like “the enlightenment” “she lights up the room when she comes in,” or the reverse “not the brightest light in the harbor,” link the idea of intelligence to light but at the same time, the light of the individual can obscure the things around them or in the words of author James Thurber, “There are two kinds of light – the glow that illumines, and the glare that obscures.”

Yet, humans, like moths are drawn to radiant personalities – we often get wrapped up in their charisma and fail to think rationally, which explains the success of totalitarian leaders. It is the job of the collective to police such individuals to protect their own rights as extreme individualism can easily turn into anarchy, yet at the same time, extreme collectivism can easily morph into tyranny. Taking both ideas to their extreme, we realize that they both have potential to do severe damage to the rights of the individual.

What’s interesting about Lerouge Knight’s work is how it forces us to confront the value we place on these two different ideas, how both possess negative and positive aspects – like the yin and yang they cannot exist without each other. A collective always needs an individual as a leader, and an individual is only an individual when contrasted against a group.

Here, the artist leaves room for us to ponder: which side of the spectrum do we lean towards? How do our actions as “individuals” affect those around us? Do we all have internal dimmers which use to regulate our behavior? Do we behave differently in different groups? Where is the line between being a doormat and a tyrant? While a society like North Korea would be considered on the far spectrum of collectivist, the US is at the other end of that extreme, yet both are in crisis to different degrees. Which kind of world do you want to live in?

1. Sophia Jowett, David Lavallee (Ph. D.), Social Psychology in Sport, Volume 10, 2007, Human Kinetics, Champaign Il.

2. Ronald Inglehart and Daphna Oyserman, Individualism, Autonomy And Self-Expression: The Human Development Syndrome, University of Michigan

3. Markus, H. R., & Kitayama, S. (1991). Culture and the Self: Implications for Cognition, Emotion, and Motivation. Psychological Review, 98 (2), 224 – 253, Kim, U., Triandis, H. C., Kâgitçibasi, Ç., Choi, S., & Yoon, G. (1994). Individualism and Collectivism: Theory, method, and applications. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc.Kwan, V. S. Y., Bond, M. H., & Singelis, T. M. (1997). Pancultural explanations for life satisfaction: Adding relationship harmony to self-esteem. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,73 (5), 1038 – 1051.

4. Peter Conrad, The Medicalization of Society: on the Transformation of Human Conditions, Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, 2007, 17-18

5. Peter Conrad, The Medicalization of Society: on the Transformation of Human Conditions, Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, 2007, P 17

6. Evan Osnos, “Crazy English: The National Scramble to Learn a New Language Before the Olympics,” New Yorker, April 28, 2008

一个部落

越过集体主义和个人主义之间的这一复杂地形

林白丽

60后和70后这样年代的人极端地以集体为中心, 之后的每一代, 80后和90后却越发的个人主义。标榜独立精神的年轻的90后与他们父母那辈之中许多仍深深眷恋红文化和集体活动的人完全性地大相径庭。

在这个价值观冲突中, 我们有必要重新审视一下集体主义和个人主义的不同概念。从最根本处挖掘出它们到底意味着什么, 而以它们为依归的社会又是怎样的形态。

在19世纪60, 70年代, 荷兰社会人类学家霍夫斯泰德对不同民族的社会价值观进行了一次广泛的调查。那时他在IBM工作, 他以各种各样的问题采访了那些员工、包括有权力、宽容、个人主义。他的发现并没有使大多数的人惊讶。大多数西方发达国家获得了很高的分数, 满分120分里加拿大获得了80分, 美国91分, 而发展中国家取得的分数非常低, 印度尼西亚14分和危地马拉6分。

据这份调查显示, 不同人看待世界有着根本不同的角度。霍夫斯泰德把个人主义解读为“对义务之外的权利的关注、对自己以及最亲近的家人的关心、个人的自主性、自我实现, 对自我成就的认定基础。”

与此同时, 如果个人无所建树, 社会并不负有责任 。而那些在艰难条件中成功的人被尊崇为“白手起家”。

个人主义者对人们之间的关系也有着不一样的态度, 当他们觉得这些关系太花时间或造成太多负担, 他们会选择放弃。而集体主义者将关系视为约束及义务, 比如你的父母在你年幼的时候照顾你, 所以你必须在他们年老的时候照料他们而不是将他们扔进养老院。集体主义文化关注上下级这种不同层次人们之间的关系, 而个人主义文化更关注朋友和同辈之间的关系。

事实上, 集体主义者实现的是社会角色, 比如为自己的父母买套房子以带给自己一种个人的满足感而不是自我实现, 互相依赖是关键而个人之间的冲突是被隐藏的, 比如说大家都不愿意提及或讨论的一些事情。

虽然个人主义者更善于讨论问题, 但他们也更容易沮丧。即使报导称亚洲大部分人口拥有抑郁基因、但仍然远远低于美国 - 社会学家认为过度诊断是一个问题。关注个人不仅意味着人们过多地考虑自己的问题, 也说明他们觉得自己有权利去尽情享受自己的快乐。

Monica Lin探讨了当社会针对我们的心理健康问题向我们施压, 我们是否有能力剔除掉所有的不良情绪, 和其他人一样快乐这一问题。

社会对于心理常态的概念已经走向医疗化, 即使是对于每个人都有所体验的普遍情绪。 比如在公共场合发表言论或对工作的忧虑, 这些对于心理健康的人来说都相当平常。这些情绪现在被冠以”社交恐惧症”或“广泛性焦虑症”, 这样的诊断在19世纪80年代很少见, 但现在却非常普遍, 部分原因即在于医药公司的促销活动。

在这本名为社会医疗化的书里:人类状况的改变, 医疗社会学家 Peter Conrad 陈述到直到1997年, 美国政府要求所有的医药生产商将药品的副作用罗列。

比如 “Scamitol会造成心脏和肝脏衰竭、紫色疹子、幻觉、刺痛感、大便失禁、(脑缺氧造成的)暂时性失去知觉。”现在医药生产商不再将这些可怕的成分写在广告上, 而是添加一个免费热线电话或是网站, 他们对药监局施压, 要求官方证实他们的药品可以用于类似广泛性焦虑症等。

这导致了一个奇怪的情况; 大型医药公司为了售出更多的药品而加速医疗化。 比如葛兰素史克在经历他们的抗抑郁药帕罗西汀销售淡季的时候, 他们游说说他们的药品可以治疗社交焦虑症和广泛性焦虑症。接着他们制定市场战略, 向患者夸大疾病的危险性和危害程度。

在双重快乐系列中, 林从堪萨斯城和旧金山开始她的调查, 在那她采访了她圈子里已经被诊断为精神疾病并且已经开始服药的人。她收集了药片样品然后做成石膏的模子, 然后用树脂以错综复杂的模式将其装在一起, 然后加以那些快乐的没有脸庞的孩子们在诗情画意中蹦蹦跳跳, 或者我们是否可以说是是田园诗般的环境中?她的调色模式里既有恬静的, 也有邪恶的柠檬黄背景与奄奄一息的灰色的花或亮粉红色、与一大片血红色的的区域形成对比。在她于2005年创作的”蹦蹦跳跳的男孩7号”中, 我们看到深咖啡色以橙绿色药丸点缀加以在显微镜下的细菌图片, 提示我们某些所谓的科学规律、运用科学的医生、医药专家是如何在无技不施地意图控制民众, 一种打着科学旗号的权利主义。

这些在Brandy Bunch1中的广告多以孩子们玩耍的情景主导画面, 精神药物用以控制行为而在绘画里的孩子们都是以一个简单的卡通人物出现, 但他们却少了卡通人物的夸张表情。而他们都没有脸 - 因为罪恶的药物让他们的情绪完全干涸。当林的盐酸哌醋甲酯2男孩正向天空踢出一个大弧度球, 女孩们都在蹦蹦跳跳地玩耍, 虽然我们经常看到这个女孩的形象消失地无影无踪 - 追逐他们原来的自己, 就像鬼魂在找它的原身。

陈航峰以他2010年的装置作品“杯子们”进入了整合和个性的探讨。表达了他对60年代的单位控制着人们方方面面的个人生活的看法, 包括住房、计划生育等。这个作品里包括了不同系列的茶杯, 典型的旧时政府工作单位, 但在现代大部分的跨国公司中却很罕见 - 仅仅能在保安室里见到。

陈航峰从上海的不同工作人员的休息室里收集了这些杯子, 即一个超市, 一家工厂和两家药房。陈航峰向这些单位里的人购买这些杯子, 但大多数的人都主动免费让给他, 拿着他们的搪瓷杯、雀巢咖啡杯、或目前流行的有过滤功能的乐扣乐扣杯。当所有人都拥有一个杯子, 但每个杯子又不尽相同并且代表了一种DIY的创造性和工人阶级的智慧。仿佛回到那个资源稀缺的时代去倾听这样一些声音。

陈航锋把许多杯子方在桌子上, 然后每杯都灌入半杯水。然后将一个锤子连接到机械上, 这种机械能反复不停敲打放有水杯的桌面, 锤子发出的震动通过桌子传导到容器上, 接着水中的涟漪被反射到装置后面的墙上。

在聚光灯的投射下, 这些洒落在杯子上的光, 营造出一种特殊的气氛, 像是一位尊贵的客人。与此同时圆柱形的形状和反射光使得杯子就像是许愿蜡烛, 这反射在墙上的光是人类精神的明证, 这样一种仿似光环闪耀着的气氛, 尽管有时外部环境如此简陋。

钱嵘的新雕塑和绘画作品带我们回归到一个更早的集体主义年代。这个作品的由一张照有一群年纪更大些的老百姓和工人阶级组成, 在陕西的黄河边上齐声歌唱, 和今年7月在上海公园里为庆祝建党90周年而合唱队相差不多。听到这些老歌手们的歌声是如此的扣人心弦, 甚至有些愤世嫉俗, 带着这样的怀恋和激情, 他们的嗓音微微震颤, 或许他们正在回望一个缓逝的年代。

与此同时, 我们经常见到有各种各样的人滥用集体主义精神作为工具, 钱嵘直指那些商业性的小利益群体经常唆摆更大的群体。我们在他2011年创作的“在集体之前”的绘画里看到一群邪恶的人正在搜寻合适的人捆绑到他们的利益链上。这个作品的灵感来自一张报纸, 上面刊登了一张几个中国最有钱的人的照片, 标题是“今年富豪特别烦”。

作品的右边是一个小盒子, 上面有一个性感扮相的女人对着一个戴着圆锥形纸帽(旧时学校中的差等生被强制戴)的男人抛媚眼。在后面写着“坦白”。审判这个男人的竟是一个二奶或妓女这一事实带来一种荒谬意味。这个男人将会自尝怎样的后果, 又或者这仅仅只是浪漫的前戏吗?

“小集体, 大联盟, ”2011, 一个方形的窄小的地方, 其中坐着不同的角色, 一些商人、一些知识分子、一些古代圣贤、大多数看起来心烦, 像是要被叫出去审问一样。在右边操纵他们的是一条鬼脸的龙和一个穿中山装的男人。戴着严厉的表情。当把这个作品和2011年的“集体主义之前”那张连同一起看时, 那群在右边的人聚结在一起, 背后的隐蔽处有一只手手持绳索, 控制着他们的命运。

鸽栅式文件分类架传达了思想限制之意, 但也代表无辜囚禁之意。小集体之中和小集体之二, 2011, 由白铁片和玻璃钢的小雕塑组成。效果是将一个立体模型和一个时代文物收藏器掺合在一起。钱嵘的雕塑做成一个穿高级军装的熊猫, 严肃的外表俨然像一个商人, 与旁边小熊猫的脸截然不同。众所周知国宝代表着可爱毛茸茸的动物形象, 但把它们和木鹰的雕塑放在一起, 加上一个戴着皮条的大乳房玩具猪、一个宝塔。对严肃的权利论断增加了些许荒谬。

虽然我们经常把集体视为一个整合的群体, 为了同样的目标齐头并进, 但在那个群体里也总有一些个人目的是冲突着的。计文于和朱卫兵将这些冲突看作是社会的机动性。在一块粗麻布的顶端, 有一群“小人”。(提及这个词是参考儒家中小人意指那些小心眼, 为一己私欲考虑的人)

艺术家做的这些“小人”仅仅抓住布, 就像在进行一场拔河比赛。在布的底部, 是另外一群“小人”, 以灵敏的特技逐步地爬升到一个点上。

这些野心勃勃的暴发户将重量加注在布上, 害怕将别的在下面的小人拉上来爬到他们头上。艺术家们以一种简单的视觉形式捕捉了在社会的种种斗争, 甚至在艺术圈, 这些已经坐上高位的群体为了自己地位的根深蒂固而争斗, 而那些年轻或说是弱势群体, 意图冲破墙上的洞来看看外面的世界。

这些身居高位的人显然不愿意放弃他们的位置也不愿意和下面的人 交换焦点。在解读这个作品的过程中, 可以理解这些身居高位的人是不会愿意与下面的人换位思考的。在解读这个作品的过程中, 有必要理解一下相对社会流动性, 意思是一年又一年工资的增加, 而绝对社会流动性是将自己的上升空间与同龄人作比较。如果一个人被雇佣为公司的ceo,他的社会地位整个就提高了, 但是他的朋友依然作为一个销售经理, 但社会地位就相对下降了。即使他朋友的工资还是跟从前一样。简而言之, 他的朋友不会继续拉着麻袋布短的一端, 材料的运用 - 麻袋布粗糙耐用但相对廉价, 表达了从贫困中爬出来, 将褪色了的裙子换成凸显身段的迪奥连衣裙。

个人及其与社会的关系这一个概念在边亦中的剪纸系列新作品中扮演一个极其重要的角色。三件作品分别命名为”再生”、“救赎”和“反抗” , 一跃进入了不可预知的人类思想领域, 探索着是否抑或是脱离它这样一个问题。

生活在一个由“道德学说利己主义”或 艾茵·兰德摘要“合理利己主义” - 以自我利益为考量事实上既合乎道德也合理, 或者采纳奥古斯特的“利他主义”观点, 以别人利益为先, 自己利益置后的道德准则。

边亦中作品中的人物似乎在通过手势和身体的姿势来为这一决定表演心理体操。在“重生”中的人物以不寻常的方式游走在树枝之间, 以展开的手臂象征着拥抱, 与此同时, 如同装饰线条般的交错着的树枝像是河流、道路、血脉或网络 - 所有将人们联系在一起的东西。在“ 救赎”中, 我们看到一个人以一种大胆的方式脱离这个网络, 正从树上跳出, 沿途也折断了树枝, 造成树皮和树枝的碎片纷纷从树上掉落。在他头顶徘徊的两只鸟似乎在传送监视之意, 但也可以暗示自由和独立。

在“反叛”中, 树转化了一种形式, “发芽”了许多的房子在树枝上。两个人气势汹汹地蓄势待发, 像贼一样等在灌木丛中。在这三幅作品中, 我们感觉到人物和树之间有一种尴尬的分离感, 他们像是在不同的画面和范围里。这些树似乎具有抽象的远距离概念以至于其间的人物似乎从没融入其中, 如同在社会范畴内作为一个利己主义者一样存活着。

这里还包含有一个有趣的象征手法“人是从树上掉下来的”人类的进化和改变是从树上的住处到平原, 然后开始人类文明。作品里的有些东西似乎像在暗示, 即使我们已经文明化, 人类却表现得和自己的代理人一样, 对自己作为集体一员漠不关心。

在以混合材料创作的沉思系列中, Robert Davis 将这一概念进一步深入化, 敦促我们做集体中有价值的一员。积极地用我们个人的力量来帮助解决集体的问题。

一直以来水都是Robert作品的中心, 而他最近的这个系列是亲历海平面上升, 毋庸置疑这个岛屿系列带给我们的是孤立的概念。他是受到17世纪的诗人约翰•多恩的影响, 以“没有人是一座孤岛”激励我们应把人类这个概念看作是像身体一样的整体, 当一个人死了就好像我们失去了一只手指或一只脚。我们需要将他人利益列入考量如同我们我们考虑切身利益一般。

因此这个布道钟不仅只是在召唤传教士, 也是在召唤教徒。所以这个钟是在召唤我们所有人。因为我病入膏肓、奄奄一息, 所以我比其他人要更关注这个问题。

在使用这个丧钟的比喻时, 他在这个需求上增加了一个病态的急促去思考人类存在的问题。Davis 的需求也一样迫切, 这个高楼和画钟的结构看起来似乎实际上它们已经沉入了白色的浩瀚海洋中, 而且似乎一切已经太迟了。

在2010年的“沉思二:集体主义意识”个人与集体之间的冲突。以一个紧紧抓住一根连接到左边烟囱拉线的人以及另一队把右边的大烟囱拉上去的人清楚地展开画面。 这些拉线创造了一个视觉与隐喻意义上的张力:人们为了得到自己想要的东西而互相斗争, 人们的内里有这样一种考虑:选择去做灵魂高洁的人还是做持一己之私的人 。

尽管这大量的建筑物看起来就像一个奇异的东西,可能修过片然后打印出来,它实际上聚集了不同的图像、冷却塔、工厂、旧时欧洲建筑 - 所有的这一切都是在刻意减少从报纸上截取照片。戴维斯花费了大量的时间翻阅报纸,因为他必须找到相同规模的建筑的原始图像。

个人剪下的图样通过铅笔、钢笔、墨水的应用而统一在画面上。Davis 还加了一些文字在上面 “我并不责怪那些被纳入一种文化里的人和独立地思考自己学着做决定, “是不知不觉但却给人类的维度对报纸的照片。Davis作品需要的能力, 我们要过细地找出证据的手在一些看起来像艺术家从距离完全机。

Davis的作品要求我们像找寻证据一般的专注度来看他的作品, 贴近着看他的作品完全是机器制品。

讽刺的是, 他的写作和细节非常小, 有时可以被更容易被拍照和放大后用电脑。这之间的对比度大、人造和制度和人力和个人是一个主题在以前的作品, Davis 探索一个试图使我们想起了个人的价值在这伟大的经济机器。

李消非探索这个问题以他精彩的录像作品“外国老板”2010和“一个车间主任”2010。检视个人与集体机器之间的激烈竞争。这两件作品是由艺术家本人的大量实践造就的, 2009年他开始采访法国和中国的小学生, 他问一些关于他们生活的基本问题。在这个系列中, 李消非采访了许多在长江三角洲的不同工厂工作的人们:印刷车间技术员、布料印刷厂的车间主任和印刷公司的外国老板。

这些采访由受访者解释一些关于他们工作的事情开始, 关于工厂里的设备、那里生产什么、然后进入更加私人化的领域, 比如受访者周末都在做什么、他们一般休息几天。很清楚他们的私人生活已经完全被工厂的工作完全占据了, 当他们休息的时候, 他们会选择偶尔出去郊游或是和朋友在网上聊天。

这个工作生活侵占私人生活的想法凸显了李消非的火速编辑力。这句话一从受访者的口中说出来, 画面就切换到急速旋转的卷桶或研磨桶, 它让流水线上的图案织布在流水线上装配生产。采访室的宁静被机器的叫嚣声粉碎, 入侵了这次谈话, 就像工作也入侵了受访者的生活一样。这里有一个有趣的对比, 在抛光钢和拉紧的大量的纸张之间, 几何力量和精确, 在机器背后人们不够专注、懒惰的本性, 外国老板那蓬乱的头发又或是印刷店的工人跟着节奏堆垛机纸。

外国老板的这段话也将重点放在工作生活和私人生活的对比上, 解释了欧洲人是怎样保有一个更健康的工作和生活的平衡状态, 而中国人总是要整天开机还要经常加班。这老板将这样的情况与以前的集体制工作单位对比, 那时的工作很稳定, 单位样样都提供。今天的新工作单位要求更高, 但给的却比以前少。在新资本主义模式下, 员工不是为了学习而在工作时间外留下, 是因为工厂需要加班又或是他们需要更多的钱?那他们工作是为了生活还是他们活着就是为了工作?

有时我们会陷入固定模式, 很快我们的行动会成为潜意识和自动。vasco在他的作品“唧唧叫, 约翰在笼子里, 装置作品, 2011”检视模仿和重复的问题。这个作品由一批电子鸟组成, 它们发出一系列的啁啾声, 旁边是一只真的八哥学它们说话。虽然八哥已经适应了模仿森林中其他的鸟, 它们很容易听懂其他的声音, 比如手机和微波的呼呼声, 在上海有只八哥学会了一个老人家清嗓的声音。

如同八哥一样, 作曲家John Cage, 也一样喜欢四周环绕着声音。他因为他的有争议的作品”4分33秒”而出名 - 仅仅是一个四分钟长的 无声片断, 为了让观众感受和思考自己所在地周围的声音。

当八哥学会了怎么去模仿它群体里的鸟, 它的运动和啁啾就被电子设备录下来, 这个反馈调节这些鸟收到了多少电压。Paiva在这里玩的是对自然生物模仿人造物的讽刺, 而人造物本身是被设计为模仿自然物的。

John Cage 这只鸟 - 尽管在领导乐团, 却也在跟着乐团而指挥, 它给了我们一个有趣的隐喻, - 任何领导者, 不论多强悍, 都会被团体可接受的一切所控制。

这个来回反馈也让我们洞悉自己是如何了解信息, 进而传递、重新推发。八哥重复那些并不是语言的声音借用了本次展览主题所涵盖的有趣的象征性。我们是否也曾重复一些我们不曾真正证实过的事情, 只是将它到处传扬, 转变形式然后将它再一次传扬。比如现在像微博这样的发布工具, 上面的内容经常是由一些主流报纸上摘下来, 然后读者就把这些文章转来转去, 但这些博文的发布者是谁?又有谁真正考证过他们的可信度?

这个来回反馈也让我们洞悉自己是如何了解信息, 进而传递、重新推发。八哥重复那些并不是语言的声音借用了本次展览主题所涵盖的有趣的象征性。我们是否也曾重复一些我们不曾真正证实过的事情, 只是将它到处传扬, 转变形式然后将它再一次传扬。比如现在像微博这样的发布工具, 上面的内容经常是由一些主流报纸上摘下来, 然后读者就把这些文章转来转去, 但这些博文的发布者是谁?又有谁真正考证过他们的可信度?

周啸虎在他的作品“疯狂英语营, 泰特, ”2010中呈现了盲目重复这一观念。作品是基于具有超凡魅力的李阳所创办的一所非传统的英语学校, 一半角色是大陆英语学校的巨头, 一半角色是语言老师, 被激发了的讲师。疯狂英语的秘方在于让学生以最大音量喊出句子然后他们可以克服自己的恐惧感。

这个项目被一些人批判, 李阳被冠以煽动崇拜和疯狂英语是一个邪教。作家王朔开炮形容它:“这是一种古老的魔幻牌, 召唤一大群人, 让他们说话很激动, 创造出一种力量强大到足以推翻山脉和推翻海”。根据Evan Osnos在《纽约人》一篇报道上, 该项目有相当强烈的民族主义色彩:“征服英语, 让中国变得更强大!”李阳的说英文的能力在宇宙中关系到个人力量, 从个人的力量又衍伸到国家的力量。”Osnos继续追踪疯狂英语集训营, 描述了他在北京发现疯狂英语有军事意味, 教师疲于带领学生喊着带有民族色彩的口号。

周啸虎有意疯狂英语的创始人去泰特做一个演出, 利用这个机会让大多数母语是英语的英国学生做他的学生。这个讲师用极其夸张的动作和表情, 要求学生以同样的元音说话.比如 time, like 和 fly 他们一遍又一遍地重复这几个单词, 在空中挥舞他们的双手, 大喊time-like-fly , time-like-fly大喊, 一遍又一遍。

通常都以“Oh”和 “So”拉长了声音, 这种带些哀嚎的声音听起来很像是醒来的魔鬼, 接着他开始介绍词语的谬论, 疯狂地以开某人的咽喉来解释疯狂这个词。有一些表情动作甚至已经到了淫秽的边缘, 像是放在嘴巴旁边的向一边倾斜的成功手势是指口交, 或者让一遍遍让人群叫暗示“高潮”(英文里 “come” 有两个意思) 不断, 这个作品也包括了对于参加者的采访比如性暗示、被操纵的感觉、我们感觉被人利用过的问题、怎样在一个群体(母语不是英语的一个)说话用以克服她的害羞。

文化异化或陌生感是这个装置作品的亮点, 作品的横幅上写着“帮助3亿中国人学习说好英语。让中国被世界知道”这讲师的发音也很的whichset性能特点的旗帜读(原文如此)”, “Help 300 million chinese speak good english. Make china widely heared throughout the world,” 帮助3亿中国人说好英文让中国在世界范围内广泛听到。”英文的词语“heared”拼错了。这个讲师发音时的重音也相当明显, 他喊出的美音有一点奇怪, 尤其是在他说像“愤世嫉俗”这样的词的时候。

通过老外学习中国式英语, 周啸虎意图推翻和打乱殖民后殖民的一种不平衡, 批判这样一种要求世界上的人们都学习英语, 但其实以英语为母语的人们并没有做出什么努力作为回报。与此同时, 这个作品也是另一种形式的文化交流, 不再是那些中国团体(那些早上做着健身操、唱红歌)向西方学习。

Lerouge Knight 以她的的装置作品“每个人都闪耀得不尽相同”2011探索了个人与集体之间的一种精彩的统一性。一个墙上的灯泡被连接到一个调光器, 可以转向左边或右边来调节光的亮度。当光最亮的时候, 观众的影子会被投射到墙壁上。在调光器旁边的墙上有这样一系列的词:

个人主义 集体主义

特立独行 追随者

自私 关怀

独创的 传统

创造性的 顺从

卓越的 谦虚的

观众们可以用调光器调整房间的亮度, 在光线明亮的情况下, 他们的身体会在墙上投射一个影子。灯泡作为一个象征物让我们回忆起许多事情, 灵感, 光亮也能跟天才、迷人、聪智联系在一起。像启蒙这样的短语“当她走进来, 她照亮了整个房间”或反过来说“不是港口最亮的光”和智慧发光息息相关, 但同时个人的光芒可以将周围别的事物掩盖。

观众可以把调光调整水平的把房间里的灯, 当光线明亮的他们的身体会投下一个阴影在墙上。灯泡是作为一个象征回忆起许多事情, 感觉的想法(这可能源于爱迪生的发明), 而且聪明的想法有关, 光存在人才吸引力或智力。像这样的短语, “启蒙”“她照亮了房间的时候, 她进来, ”或“不亮的光扭转在港口的想法, “链接智能光, 但同时针对个人可以掩盖的东西给他们周围的事物。美国作家詹姆斯·瑟伯曾经说过, “有两种光, 光辉照亮了热情, 强光, 模糊了。”

甚至从物理的角度来说, 盯着一种亮光, 比如太阳一会儿, 一段时间后我们的眼睛已经难于集中在我们周围的事物上。事实上人类很像飞蛾, 很容易被耀眼的个性吸引 - 我们常被他们的个人魅力所着迷, 却失去理性的思考 - 有些人可能认为希特勒成功。警察整个机体是为了保护个人的, 但极端的个人主义会转向无政府状态, 与此同时非常极端的集体主义也可能变成暴政, 将这两个概念极端化, 你会发现他们都有潜在的力量严重地损害个人利益。

Lerouge Knight 作品有趣的地方是她促使我们面对这两个不同观点的价值, 我们怎样同时保有积极和消极的两方面, 就像阴阳不可以单独存在。一个集体总需要一个个体作为领导, 而个人仅仅只是个人, 当对一个群体像比较时“群体类似行为”

她在这里留下余地让我们深思:Lerouge Knight 的作品也许是一个很好的结尾, 因为她迫使我们去思考自己的价值观, 我们学到了哪方面?作为个人我们的个人行为是否会影响到身边的人?我们身体内部是否也有一个调光器去调整我们的行为?在不同的群体中我们是不是表现得不尽相同?逆来顺受和残暴不仁之间的界限在哪里?北朝鲜中央的社会多是集体主义者, 而美国是另外一个极端。他们各有各的失败。你愿意住在怎样的世界里呢?

1. Brady Bunch是一个美国70年代的情境喜剧关于一个完美的家庭

2. 用于治疗多动症和注意缺陷多动障碍症的药物