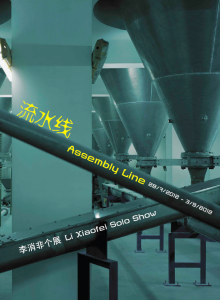

In the Age of Mechanical Reproduction

Li Xiaofei’s “Assembly Line” series examines a number of complex relationships between man and machine, management and labour and the individual and society.

Though often attributed to Henry Ford, we can find the hints of the assembly line in much earlier times. Adam Smith referred to the idea in discussing the production of pins in “The Wealth of Nations,” and Qin Shi Huang employed an assembly-line type process in the production of the Terra Cotta Warriors where each part of the soldier was made by a different workshop then later assembled.

China, therefore, makes a great stage to explore the concept of the assembly line. While college students take courses in advanced manufacturing and management theory, they are still nonetheless forced to take the compulsive courses in Marxist theory or 马克思注意 “ma-ke-se-zhu-yi.”

Li’s work not only engages in the lingering legacy of Marx but also brings to mind a number of other ideas about worker motivation and management theory. The work is not a didactic unified message but a plurality, a nuanced exploration of the relationships between management and labour, between man and machine, personal and private life, the individual and society.

These videos juxtapose documentary style interviews with both factory workers and managers spliced in with luscious imagery of spinning wheels, and moving parts often lit in an otherworldly glow — hues of light and patterns of movement that we seldom witness in our everyday lives. In fact one of the work’s biggest appeals is its ability to guide us into spaces which are usually out of bounds and Li had to rely upon his extensive network of friends and acquaintances in order to gain entrance to these spaces. Often it would be his cousin’s friend’s brother’s colleague or some other form of six-degrees-of-separation serendipity which lead him to these spaces of industrial production around the Yangtze River Delta.

Some works tell the story from the management point of view. For instance, “A Department Manager,” a diminutive woman who specializes in pattern printing talks about the ins and outs of the factory, how they had to move their workshop to make way for the building of the2 Expo, how she got her technical certificates, the difficulties of holding onto skilled workers and the migrant population. This is all set off against a symphony of movement: hard metal parts turn and crank. Coated in a soft layer of cotton fuzz, a number of levers move up and down like insect legs gingerly walking, while various other machine parts flutter like butterflies. There is something truly organic and alive in the way the machines work giving the façade of aliveness to something cold and inhuman.

This contrast between the cold and hard and mechanical and the soft, cloth and human comes through even more strongly through the soft countenance of the Department Manager — her supple skin and freckles speaking to a youth gone by.

She also expresses something of a tentativeness, something subtly revealed in her face during the pauses while she is not speaking. Li captures these moments by having the camera turned on without letting the subjects know he’s filming, thus forcing them to let down their guard and let their thoughts wander. While the economic system may regard the worker as a mere labor input, Li depicts them as humans lost in the realm of self-reflection — expressing a bit of shyness, a wistfulness or, more often than not, a forced cheerfulness.

Such scenes are contrasted with the mesmerizing rhythms of the threads moving back and forth, each string feeding into its own path. Like the machines, the humans require a high level of precision — where every individual worker must perform a movement at a uniform speed, with no deviation, in order to prevent the production line from grinding to a halt.

Here I think it’s interesting to examine the relationship between man and machine which is constantly being re-negotiated throughout history. In writing about how the factory rhythm changed the pace of life in the 19th century, authors Lex Heerma Van Vosssays et al say that:

Irregular “task-based work gave way to regularized time discipline, with the factory clock (or bell) determining the workday. Moreover, what was new was that the speed of the power-driven machines determined to a large extent (though not fully) the pace of work. While technical control was taken to a more sophisticated level by Henry Ford, it first was pioneered in cotton textile factories.

This sets up an interesting paradigm where machines created by humans have now become masters of their creators. Of course there is still one human (usually a foreman) capable of pulling the lever and shutting the whole thing down but there is something deeply dehumanizing about this work, which replaced the more highly-skilled artisanal and mechanical labour of the 19th century, with more low skilled “supervision” based jobs.

Marx talked about this in Das Kapital, saying that “…the laborer becomes a mere appendage to an already existing material condition of production. ”

Interestingly enough, management theory proposes that there is an optimal level of automation in a factory. Too much automation and the humans become complacent and stop paying attention. They need to be kept involved in the process of production in order to fall asleep at the machines.

Li’s other work “A Sales Manager,” also takes place in a textile factory, but in this factory there is a slightly-greater level of skill required of each worker and most of the floor space is taken up by sewing machines. This piece presents a strong aesthetic break from the other video pieces with a long pan across the factory floor (almost as if the camera itself was placed on a conveyor belt) where piles of cloth blot out the images of the worker, cut in with an interview with a Belgian sales manager. In the video she talks about the regulatory difficulties of running a business, having her dormitories demolished because they were built in a commercial property, and the problems of holding on to workers.

The video also includes an uplifting story of how one of the workers taught herself how to use a printing press and was therefore able to greatly increase her annual salary. The manager presents a much softer, more progressive side of factory life, talking about how her workers get awarded for loyalty, their salaries improving with seniority — a benevolent gesture which also helps the factory with staff retention. She talks about how beautiful the dormitories were and about how her workers pledged that they would stay with the company as long as they were in China. Interestingly though, the images we see of the factory floor look no different to any other factory. Is this attractive sales manager, lit by graceful natural light, presenting us a curated vision of the reality of her factory? Is it the model work unit she portrays it as? The question hangs tentatively in the air.

Here we can see Herzberg’s “Two Factor Theory” or “Motivation — Hygiene theory” at work. In it he states that worker satisfaction is linked to the nature of the job and its ability to grant a sense of fulfillment and personal growth, high status etc, i.e. the worker who taught herself how to use the printing machine. But even for those doing menial tasks, the “hygiene” factors such as company policies, salary, working conditions and the management’s ability to treat workers with respect and dignity can help create satisfaction.

“A Printing Press Operator” gets at the heart of these issues exploring the life of a young man who was underpaid for his work, only earning 300 RMB a month when he first began his job. But later, his salary was adjusted to 3,000 RMB a month which was more in line with industry standards. This brings up Marxist ideas about surplus value, i.e. the print factory boss must have been brining more than enough money based on that wage to support the workers’ needs. The fruits of the rest of the labour, the long hours, days and nights doing special rush orders for clients went into the boss’ pocket. We see here a modern day picture of what Marx would deem capitalist exploitation with the youth enduring a rather lonely existence, going from night shift to day shift, going home and cooking for himself and seldom going out. The only little bit of joy in his life is chatting with his Internet friends who he feels are more genuine as they possess no ulterior motives. It’s in this work that the conflict between the demands of the factory and the demands of the individual come into relief.

These themes are highlighted by the imagery. The video (as in many of Li’s works) begins with the deafening hum of machines. In the opening scene we see the printing press, actually pressing down on pieces of paper, pushing the stack of paper lower and lower. In another scene a red flashing light indicates urgency — the demands and pressure of the job. At the end of the video while the character talks about his lonely social life, we see a black grill which looks almost like a brazier with an orange glow emanating from it, which in the final seconds of the video flickers out to black.

“A Foreign Boss” also conveys this sense of one’s time being eaten up by the needs of the factory. The video opens with the image of a spinning spool of paper (perhaps a stand-in for a clock) which slowly gets larger and larger as the paper accumulates. The “boss” who works at a factory which makes paper for cigarettes, talks about his first days in China in the 80s when the country was poor, and the living conditions basic. It’s a narrative of change and he talks about the frenetic pace of factory with the constant jangle of cell phones versus the quiet life of German workers who needn’t work nights nor weekends. He talks of the bar in his hometown which has remained in a time warp for the past 25 years — all the while China has been barreling ahead. The final minutes of the video show a woman in a drab green uniform and a hairnet standing stock still watching paper feed onto a spool. The only movements she makes consist of a minute fiddling with something in her hand. The spool itself seems at once to be spinning but also to not be moving at all. An apt metaphor for progress no doubt.

Li emphasizes this concept of moving and stillness in a series of atmospheric video works (Assembly Line Nos 1-9) which depict almost stationary objects which display very slight hints of movement. One depicts the aforementioned factory worker. Another depicts a monumental 100 m tall, coal power-plant cooling tower, with smoke languidly billowing from its mouth. Perhaps some of the most striking of these videos are those which depict an iron ore beneficiation plant whereby iron ore is extracted through the use of very hot liquids. In it, we see a molten river of silver bubbles flowing up and down. Despite the beauty of such shots we can’t help but wonder what happens downstream of the iron ore beneficiation plant, thus brining up the perennial conflict between the needs of business and the needs of society as a whole.

Li then turns his head to another system in “A Women’s Federation Director,” where a woman working at a factory which produces laminate flooring talks about her previous job at the Women’s Federation, a government organization dedicated to dealing with women’s health, social and reproductive issues. The organization was also known for it’s work in enforcing the One Child Policy and she talks about brining women in to have intrauterine devices installed, about how migrants have trouble going to school without a proper residency permits, but also the need to do her chosen job well. By juxtaposing the stories of her previous job with the images of the bustling factory we are forced to make the connection between production of goods and production of children, of quotas of systems and the role that population control plays in the grand economic plan. In the last moments of the video, against scenes of the dimly lit factory we hear her proclaim without irony that her biggest ambition is to raise her daughter well.

Though many artists and journalists have documented factory life (for instance Leslie Chang’s insightful book “Factory Girls,” Edward Burtynsky’s “Manufactured Landscapes” and Jin Jiangbo’s photographs of empty factory spaces), Li has created a fascinating body of work which marries the documentary elements, a charisma of movement and color, combined with deep philosophical musings about the systems around us.

Perhaps one of the best examples of this is “A Workshop Director,” which takes fabric printing factory as its subject matter. The video is filled with sepia-toned scenes of large elongated barrels rumbling along, with steam escaping, like a scene from the industrial revolution. Another scene depicts water dripping off of the reels as if it forms one continuous sheet, glistening on the plastic, suds frothing on the reels. A mesmerizing pattern of red wheels turning threading yards of black cloth between them is set to a soundtrack of squealing metal parts. The images of the older equipment are paired with dialogue about the factory’s history, meanwhile talk of the present is paired with images of modern printing equipment — flying reels of electric blue spotted fabric reflected by a mirror which creates an almost kaleidoscopic effect. The scene looks almost like a river and indeed the theme of change is a thread which runs throughout the whole work. Even the title of the series “Assembly Line,” has poetic resonance in Chinese as the “flowing – water – line.” It conjures up ideas of rivers, progress and time — and reminds us that regardless of the desires of the individual, the production line stops for no one.

By Rebecca Catching